Interview with Fiction Writer, Poet, and Essayist

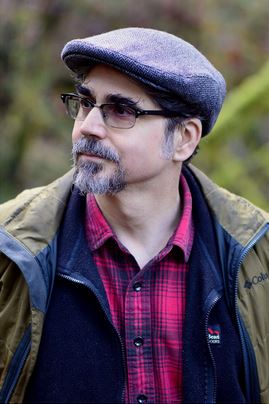

Jeff Fearnside

Jeff Fearnside

On August first, Jeff Fearnside’s collection of linked essays, Ships in the Desert, will be published by the Santa Fe Writers Project.

From 2002 to 2004, Jeff served as a U.S. Peace Corps volunteer teaching English in Kazakhstan, and he ended up living there for almost four years. During that time, he worked in Kyrgyzstan as well, and he traveled along the Silk Road throughout Muslim Asia.

In Ships in the Desert, Jeff takes us to the heart of his experiences in Central Asia and considers how they shed light on such universal issues as environmental degradation, and religious and cultural intolerance. To quote a description from the cover of the book:

“Fearnside creates a compelling narrative about this faraway land and soon realizes how the local, personal stories are, in fact, global stories. Fearnside sees firsthand the unnatural disaster of the Aral Sea—a man-made environmental crisis that has devastated the region and impacts the entire world. He examines the sometimes controversial ethics of Western missionaries, and reflects on personal and social change once he returns to the States.”

Recently, Beth Castrodale of Small Press Picks had the pleasure of interviewing Jeff about Ships in the Desert. (In 2017, she reviewed his story collection Making Love While Levitating Three Feet in the Air, praising “its deep explorations of diverse lives and experiences” and “its immersion in place.”)

BC: In the title essay, you take us deep into the crisis with the Aral Sea, considering the human factors behind the sea’s dramatic shrinkage, and reflecting upon what must be done to try to mitigate such environmental devastation everywhere it occurs. As you discuss in the book, “everywhere” includes the United States, with our depleted Ogallala Aquifer and our disappearing lakes. And you note that not taking action against such crises might lead us to water-scarcity issues so dire that they could spark wars.

At one point, you write: “As we have diligently sought to understand the Aral’s disappearance, so we must also diligently seek to understand our behavior. … But while much emphasis has been put on what it might take to save the Aral—more money, better dam projects, improved irrigation technologies—I’ve only read hints of the most fundamental part of the solution: a complete change in our attitude toward nature.”

Can you say a few words about what such a change in attitude might entail? Are you hopeful that we can achieve such change?

JF: I find our attitude toward nature downright puzzling in both large ways and small. For example, many people will carry a six-pack to the beach or forest with them but then not bother to carry the empty cans or bottles back for proper disposal. Why not? I’m not sure it can always be explained away as thoughtlessness. It seems to be part of our larger view of what nature is to us. We treat the wilderness as if it were our plaything, and like with all playthings, we neglect it when we become bored with it and ultimately forget about it. We act as if our finite planet contains infinite and inexhaustible resources to be exploited. Why do we do this? I believe it’s because we feel separate from nature. So the biggest thing we need to change is our idea of what nature is and our relationship with it.

When I’m in nature, I acutely sense deep intelligence and consciousness all around me. And it’s clear that I am part of this intelligence and consciousness and they are part of me. I am a water molecule moving through water. Sensing that, it makes it difficult or even impossible for me to do certain things to nature, such as pollute or exploit it. There is a recognition that whatever I do to nature, I really do to myself. It sounds mystical, but it’s really commonsensical. We used to have some measure of this common sense. “Don’t piss in your own well,” the saying went. That’s a form of environmental awareness we seem to have lost, though I’m not claiming we were better environmentalists in the past. I’m just not convinced we’re necessarily better today. We have more knowledge, yes, but we also leave a considerably larger carbon footprint than ever before. And our wells, the water and land and skies we rely on for our very existence, have been soiled.

As to whether I’m hopeful we can correct this by connecting with nature and our own inner natures again—yes, I am, though cautiously. That sense of wonder I feel about the world isn’t something special only a few can access. It’s part of our natural human heritage. If I can feel it, anyone can. And the more people who feel it, the greater a chance we might improve our relationship with nature, for we want to work at a relationship when we care about the other in it.

Yet it will take all of us working together. A few individuals, however brilliant and highly trained, a few groups of people, however earnest and hardworking, can’t make the difference that’s needed. Corporations are going to have to be on board. Countries are going to have to learn to work together. We’re not doing a very good job of that right now. I’ll be frank: on most days, I don’t believe we’re doing a very good job at much of anything. But I remain an unabashed believer in our human potential. Whatever hope I have lives in the idea of our coming together, starting here, now, wherever we’re at, with whatever we’ve got.

BC: I was really struck by your observation that we tend to put too much faith in technology to solve environmental (and other) problems. What have some of the consequences of this been?

JF: I specifically find it ironic that we often rely on technology to get us out of jams that were created by technology to begin with. One example I use in the book is how we continue to create highly toxic and long-lasting waste material from our nuclear power technology because we’re counting on some as-yet-undeveloped technology to be able to store this waste safely someday in the future. This strikes me as stubbornly one-minded thinking. So one consequence of our faith in technology has been loss of a multidimensional, creative approach to problem solving. We often no longer aim for the holistic or simple. We’re locked into the idea that technology is the be-all and end-all, and this tends to draw us into increasingly artificial and overly complex approaches to problem solving. I mean, to figure out how to colonize Mars, as some are proposing, so that we have a home after we’ve ruined Earth? Why not just treat Earth with respect so that we can continue to live and thrive here? That would be much simpler and more holistic.

Another consequence of our faith in technology is that in seeing it as our savior, we stop working to save ourselves. Technology is a tool, and any tool is only as good as the person using it. However, we worship material things and give short shrift to intangibles such as our inner, or what might be called spiritual, development. I’m not talking about reading more self-help books, although most of those are probably harmless enough. I’m talking about meaningful inner development, the kind that leads to an understanding of our place in the world and connection to all living things. When you know that, it makes it harder to make harmful decisions. Right now, our decisions are often disconnected from our essential selves. We want to be good, kind, moral, or whatever, but then we fall back on easy habits without thinking through the consequences.

By the way, I’m not against technology! Rather, I’m for a more balanced approach in our thinking that will allow us to use technology as one tool among many, not the sole tool at our disposal.

BC: The title essay is based not only on your own experience but also on thorough research. How long did it take you to conduct all of that research, and were there any particular sources that were especially revelatory to you?

JF: I knew from the beginning that research was going to be important to that essay in particular and the book in general. I didn’t want to write a straight travelogue. I didn’t want to write a straight memoir. I didn’t want to write a straight anything! I wanted to relate personal stories, yes, and I also felt I needed to bring in some ethos, an emotional appeal, so there was going to be some philosophy as well. But I wanted everything to be grounded in science and facts, and that requires research. I can’t tell you how many hundreds of hours I spent on that aspect alone of writing the book. I wanted it to be accurate and consistent. It had to be.

The most revelatory sources to me personally were ones that only made their way into the book tangentially, discretely, and those were the ones on Sufism and the role of women in Central Asia. I learned a lot about both subjects and may write about them more directly someday.

But the core of this book was always in the environmental themes of the central title essay. The many, many sources I consulted on the Aral Sea disaster weren’t necessarily revelatory—the disaster has been known for a long time—but sifting through it all and trying to pick out the highlights, so to speak, in order to create a broad yet reasonably detailed and comprehensive picture was definitely surprising. The scope of it was even larger than I had initially thought it would be, and the roots of it ran even deeper. That’s the lesson we need to keep in mind when facing environmental challenges today. Surface actions, no matter how immediate and showy, aren’t going to work. We need to address the root issues, and those are primarily human issues: greed, addiction to luxury, addiction to power, the need to control others and our environment.

BC: In the essay “The Missionary Position,” you discuss the religious missionaries that you encountered during your time as a Peace Corps instructor, and how their work raised some ethical questions for you. For example, what are the perils of presenting certain things as “truths” that need to be accepted without question?

With this question in mind, and speaking from the point of view of a teacher, can you say a few words about best practices for educators? Specifically, how can educators help to empower students and treat them as active, independent learners, as opposed to making them feel that they are being preached to?

JF: One must constantly be aware of the tendency to preach, especially as an educator. It’s easy to fall into the “sage on a stage” trap. Now, some students like this. I actually had one who told me I should lecture more! However, I much prefer a more interactive approach. To treat students as active, independent learners isn’t difficult. Just ask questions. Talk with them. Most importantly, listen to what they have to say.

I’m not going to claim I’m special or a model teacher. I do enjoy teaching because I like people, and students are, of course, people first and foremost. It’s enjoyable to be around them. I’m not afraid to learn from them—in fact, they know more about certain subjects than I do. If I can help them understand and appreciate and value writing more, then we’ve had a fruitful relationship. That to me is how you empower anybody, not just students—treat them as fellow humans deserving of your respect. What could be more empowering?

BC: In the essay “More Than Tenge and Tiyn,” you discuss how some of your students in Kazakhstan were reluctant to apply for educational grants because of corruption in the system. One student told you, “Everyone knows you have to pay a bribe to win.”

Later in the essay, you observe: “Just as my students felt helpless to change anything in their country, many people in my country, including me, now feel helpless to change what seems a gigantic, impersonal, well-protected, and immovable system.”

Do you have any advice for overcoming such feelings of helplessness, or for addressing those feelings constructively?

JF: That’s a great question. With all that’s going on right now, from climate change to COVID, from the war in Europe to the rise of fascism around the world, I think many people are feeling helpless to effect any meaningful change. I have to admit I’ve felt this way too sometimes. I came to the realization that I had to keep trying because I would be dishonest to myself if I didn’t. Feeling helpless is a form of deceit, because it’s telling ourselves there’s no place for us in the world, which isn’t true. We all have unique gifts to offer.

So I guess my best advice would be to stick to who you are and what you know to be right, though this has its own issues to be aware of, for what’s perceived as “right” can be highly variable. I believe we’re all propagandists, as I write in my book, but there’s clearly propaganda that’s open and enlightened and propaganda that’s intended to deceive and distort, and we’re being inundated with the latter right now. We need a lot more people to propagate—to grow—positive things in this world.

I don’t pretend to have all the answers. I don’t know how everything is going to turn out. But if I waited to know the outcome of everything before acting, I would never do anything. Action doesn’t require knowledge of the outcome, only a vision of it. We feel helpless not necessarily when the present is dark but rather when the future seems dark as well. But since the future is always in flux, there’s always the opportunity to shape it. Knowing that naturally leads to constructive action, I’ve found. That doesn’t mean we’ll always realize our visions. But striving toward them is one of the best antidotes to feeling powerless. In a poem about being a writer, Marge Piercy says, “Work is its own cure.” I would expand that to cover life more generally and say, “Striving to achieve your vision is its own cure.”

BC: In the essay “Place As Self,” you make this great observation that when writing about place, “we seek not so much to define that place but to determine our place in it and in the larger world.” Speaking as a travel writer, did you develop a lot of your insights about your time in Central Asia retrospectively—in other words, with the benefit of years—or were the seeds of many of these essays planted during your time in the region?

JF: I’ve always seen myself as a place-based writer, even if I might not have used that exact term early in my career when it wasn’t as well-known and defined as it is now. It’s just part of who I am. I can’t help but to feel the essence of the places I live in or even visit—they have real personalities to me just the same as people do. And I’ve always been drawn to other cultures. In high school and as an undergraduate, I loved hanging out with the international exchange students. I made a number of good friends from various countries all over the world. This wasn’t done consciously on my part. I naturally found myself gravitating toward these friends. I enjoyed their wider views, their different perspectives.

But living overseas myself certainly changed my outlook on many things in life, including writing. Living in another culture challenges all of your assumptions. It’s the single best experience I’ve had in terms of personal growth, and I highly recommend it. I had long talked about being a citizen of the world, but I really felt like one while living overseas, a feeling that has remained strongly to this day. So my writing comes from that place now more than ever.

BC: Is there anything else that you’d like to say about the collection, or that you hope that readers will take away from it?

JF: I hope that readers will come away with a sense of the smallness of the world and interconnectedness of everything in it. Culture doesn’t know borders. The world is a melting pot of customs and faiths, and people are fundamentally so much more alike than different, in both our strengths and our weaknesses. Pollution doesn’t know borders. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are landlocked countries, two of the farthest from an ocean, but toxic chemicals from the Aral Sea are spread as far as the Pacific. The burning of the Amazon forest affects the entire planet’s atmosphere.

I hope people will want to rise and take positive action to change the trajectory we’re on. We’re living in unprecedented times, I think the most important in human history. Yes, challenges have been a constant of our history, but never have so many humans been involved—our global population is eight billion people, eight times what it was in 1800! It took us more than two million years to reach our first billion; we’ve added another billion just in the last decade. So everything that happens affects more humans than ever. All the effects of climate change we’re seeing now—floods, wildfires, drying lakes and rivers, rising sea levels and disintegrating coastlines—impact more people than were even alive just two hundred or even a hundred years ago. As I note in the book, it’s estimated that four billion people live in areas of severe water scarcity at least one month per year. And that figure is projected to grow to six billion people in less than twenty years. We don’t have the option of remaining complacent.

Mainly, I hope people realize that the earth doesn’t need us; we need the earth. It was here long before humans and will likely be here long after we’re gone. So our efforts to fight climate change are not to save the earth. It’s to save ourselves. Collectively, are we up to this task?

BC: Thanks so much for taking the time to speak with me, Jeff! It truly was a pleasure to read your perceptive and beautifully crafted book.

JF: Thank you, Beth, for your extremely thoughtful, insightful questions. I appreciate your interest in these issues.

To learn more about Ships in the Desert and to pre-order the book, visit this link.

About the Interviewee:

Jeff Fearnside is the author of two full-length books—the short-story collection Making Love While Levitating Three Feet in the Air (Stephen F. Austin State University Press) and the essay collection Ships in the Desert (forthcoming from SFWP)—and two chapbooks: Lake, and Other Poems of Love in a Foreign Land (Standing Rock Cultural Arts) and A Husband and Wife Are One Satan (Orison Books). His stories, essays, and poems have appeared widely in literary journals and anthologies such as The Paris Review, Los Angeles Review, Story, The Pinch, Forest Under Story: Creative Inquiry in an Old-Growth Forest (University of Washington Press), and Everywhere Stories: Short Fiction from a Small Planet (Press 53). Fearnside lived in Central Asia for four years and has taught writing and literature in Kazakhstan and at various institutions in the U.S., currently Oregon State University.