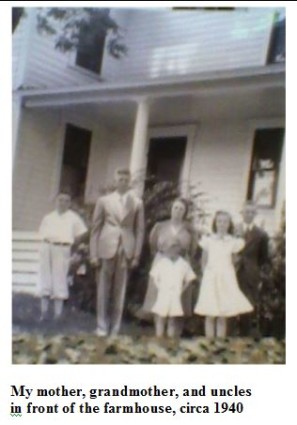

I’m getting back up to speed with my small-press reading, and I’ll be posting more reviews shortly. In the meantime, in honor of my dear mother, Barbara Castrodale (1928-2015), I thought I would share this essay about a place central to both of our lives.

The farm in Washington County, Pennsylvania, where my mother grew up, is the setting for much of my second novel, Marion Hatley. It was also the setting of a novel I attempted in my twenties, a work now (justifiably) moldering in my cellar. And it has made cameo appearances in my short stories.

It was—is—a small farm, taking up just 130 hilly acres of southwestern Pennsylvania. The home at its center is likewise modest.

“I can say that it was not the most comfortable place,” my mother wrote in her memoirs. “It was a frame house with eight rooms, one bath, and front and back porches. There was a basement, which had a floor that was partially dirt. There was no insulation in the walls [until] I was in high school (around 1944 or 1945). … As a child, I can remember getting out of bed in winter, hurrying down the stairs to the living room, and getting in front of the fireplace, the only one in the house, to dress. The windows would be covered with frost so that you could not see out.”

The times I spent on the farm, which thankfully remains in my family, have accounted for but a small fraction of my life. During the summers of my childhood, my parents, brothers, and I would travel there for reunions and other gatherings. With time, however, as we kids took on lives of our own and as our parents grew older and frailer, those visits became less and less frequent.

What, then, might explain the persistence of the farm in my imagination and in the stories I’ve been most drawn to tell?

One thing that struck five-, then ten-, then thirteen-year-old me was the seemingly limitless wonder of the place; it imprinted itself on my mind. At the time of my earliest memories, my family lived just twenty miles east of the farm—on a neat half acre in a fairly new suburban development. Our home was a place of rules and order, the only pets a trio of gerbils who scuttled about in an aquarium lined with wood shavings.

But once my father turned our Dodge off the country road and down the rutted, winding lane that led to the farmhouse, we might as well have entered another world. All around us, as far as we could see, was rolling land planted with crops or left alone, and distant stands of trees. No limits. And once my brothers and I were out of the car and off with our cousins, rules and order—even the very idea of parents—seemed to vanish. We roamed free for hours on end, following our cousins’ lead or our own curiosity into mysteries, or to what felt like the edge of trouble.

Where does the path through this field lead? We followed it to find out.

Why are all these animal bones in this pit? No one could say. With sticks, we hoisted the skulls of cows and steer, as if reviving the dead.

Which smells worse—the chicken coop or the hog pen? It was a draw.

How fast will this dirt bike transport my cousin and me to the top of the farm’s highest hill? Faster than I’d ever gone anywhere.

What would happen if I jumped through this hole in the hayloft, into the bales way down below? Here, self-preservation trumped curiosity.

Just as intriguing to me—just as lasting in my memory—was the farmhouse itself. Built around 1880, it was far older than my parents’ house and all the other homes I was accustomed to. Lacking any Victorian ornamentation, and updated here and there with paneling and shag carpeting, the rooms nonetheless betrayed their age. Beneath the carpeting wooden floors creaked, and the shadows of the rooms suggested layers of lives and years. At night the room light had a yellowed quality, and at all hours the smell of the farm persisted (pleasantly) indoors, mingled with the essence of aged wood and plaster, and of year after year of cooking. Here, I first lost the sense that any room I entered, anywhere, could only be about the here and now, existing in isolation from the past.

Because my mother told and retold stories of living in this place, I began to adopt some of her memories of it, like this one:

With such stories in the back of my mind, I began to populate my own mental pictures of the farmhouse with family members who had moved away from it or died. And it wasn’t such a big leap for me, as a young writer, to imagine other, invented lives being played out there, too. I filled the rooms with characters I hoped might be familiar to my mother, uncles, and grandparents, if not necessarily admired by them.

For some odd reason, I was especially taken by the little bedroom above the kitchen, where a number of hired farmhands had slept over the years. The idea that the hired men might share a roof, even meals, with the family but also be kept at a businesslike distance stayed with me. And in some small way it planted one of the seeds of Marion Hatley, whose eponymous main character takes up temporary residence in a space like the one in my memories:

In fact, the actual room had no peeling cornflower wallpaper, no bulky armoire, writing desk, or sewing machine. But I tried to be true to the incidental comforts of the space, to its sense of contingency.

In describing the importance of the family farm to my writing, I don’t mean to romanticize country life or to express regrets about not having pursued it myself. Like Marion Hatley, I am happiest in the city and feel unmoored when I’m away from my adopted one for too long. But it isn’t country life in the abstract that has loomed so large in my imagination all these years; it is a particular place in the country, a place with a history both familiar and somewhat mysterious, that has left such a lasting mark on me. I am thankful that I was free to turn myself loose in it, body and soul, at just the right time in my life.