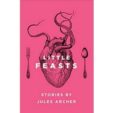

The “little feasts” in this darkly intriguing story collection are works of flash fiction that explore a variety of appetites: the kinds that few people would discuss over dinner, but that say much about the scope and strangeness of desire, and about its potential to endanger or save us.

In “Hard to Carry and Fit in a Trunk,” the central character fantasizes about becoming thin enough to fit into the trunk of a car: the car of any stalker she might attract. “She’s prey,” the character reflects. “Or she would be if she could drop those last fifty pounds. … She walks down on the train tracks, deep in the heart of downtown, offering herself. But no one wants a fat girl.”

In “Prettier Things,” the narrator becomes captivated by a neighbor, not only because he’s handsome, handy, and polite but because of what she notices going on at his house. Although he invites a series of women into his place, none of them seem to leave. The only things the narrator does see leaving are “oddly-shaped packages” that the neighbor drags out the front door and into the bed of his pickup truck. Over time, she finds herself taking pleasure in being silently complicit with him, thinking, “I practice the story I’ll tell the press when the cops find him out. But until then, he’s mine.”

Several stories in Little Feasts, including the previous ones, encourage critical reflection on our culture and ourselves. Reading “Hard to Carry and Fit in a Trunk,” for example, it’s hard not to think about the wide-ranging consequences of body shaming, some of which, surely, are as dark as those experienced by the narrator of that story. And for me at least, “Prettier Things” prompted some reflection on what the interest in true-crime stories says about the audience. If this interest doesn’t exactly make the audience complicit with the killers portrayed in these stories, is it at least a bit unseemly? (Disclosure: I’ve been a true-crime fan for years.)

In inventive and unexpected ways, other stories in Little Feasts explore the appetite for vengeance–particularly against men who prey upon women.

In “The Ice Cream Cone,” a woman imagines her enjoyment of this treat being interrupted, in typical horror-movie fashion, by a stalker who begins to chase her. As she imagines the chase, she reflects on the harassment, sexual predation, and violence that she and her mother have experienced in real life. Then she thinks: “because this is a horror movie, you forgot you still have an ice cream spoon in your hand, perfect for scooping the guts out of trash men.” In her mind-movie, she uses the spoon to take down her would-be attacker, and although this may be a fantasy, it sustains her. It’s also a reminder of a crucial power she’s developed: to survive and learn from all the dangers she’s been exposed to.

In the darkly humorous (and deeply satisfying) story “Skillet,” the weapon of choice is not an ice cream spoon but a cast iron skillet that has been in the narrator’s family for generations. As the narrator cooks with it, her mother gives this advice, foreshadowing the skillet’s darker history: “You meld the ingredients the way you would strike a skull–carefully.” Also, the recipe the narrator is using, from her great-great-grandmother, includes instructions that go beyond cooking: “Swing high, it says, stained with red.”

It turns out that over the years, the women of the family have indeed swung the skillet high, to put an end to various husbands or lovers. And it seems the narrator is poised to carry on that tradition. When her mother takes a new, violently abusive lover, the narrator picks up the pan, with something other than cooking in mind.

Another story of vengeance (and one of my favorites in Little Feasts) is “Anne Boleyn Could Drink You Under the Table.” In it, the second wife of Henry VIII has been reincarnated as an “over-educated college student in some preppy East Coast town.” She’s kept her taste for mead, which she carries around in a Yeti tumbler, and she’s taken a job as a bartender “based solely on the uniform. Though tavern wench isn’t the right costume for the time period she remembers, nor for her class, it’s the closest she can get to her roots.”

She imagines that Henry might have been reincarnated, too, and that he’s “ready to marry, ruin, do it again.” She also imagines how she might break this pattern–and break him–with a little help from her mead. This story is captivating, not only because of its revenge plot but because of its implicit criticism of how Anne Boleyn (like other women of history) has often been portrayed by men in the academy. As she sits slumped in her seat during a European history lecture, she thinks:

In a fun-to-read interview with Sara Rauch, Little Feasts’ author, Jules Archer, offers some insights into what inspired the stories in the collection:

The characters are right, and readers will no doubt be intrigued by their glimpses into these stories’ strange, often unsettling worlds.

Would My Pick be Your Pick?

If you're interested in ________, the answer may be "Yes":▪ Flash fiction

▪ Horror fiction

▪ Stories of the strange or unconventional